Over two Tuesday nights in February, the Jacksonville City Council engaged in one of its more contentious debates since the board was reshuffled in last year’s elections.

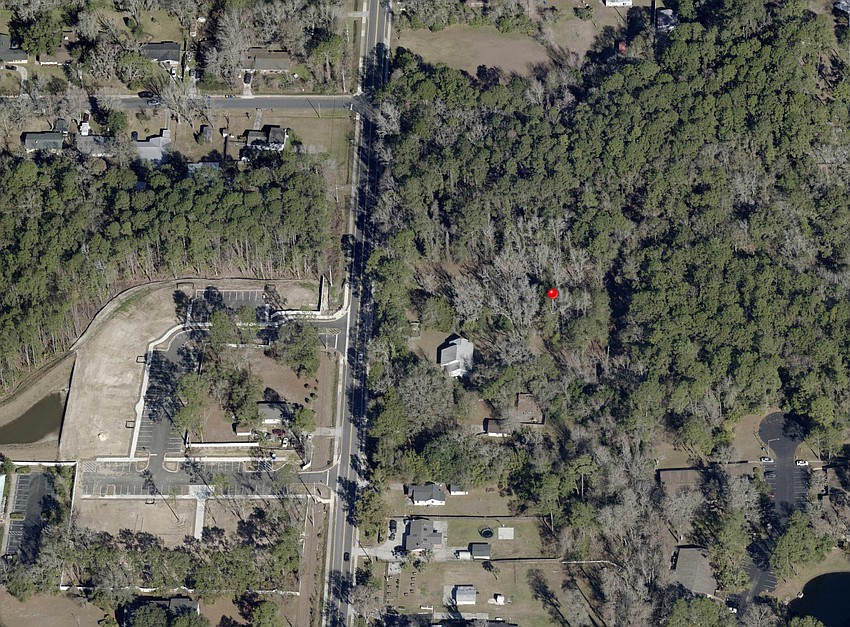

The subject was a proposed workforce housing development at 10939 Biscayne Blvd.

On an undeveloped 5.4-acre property, developer Lisa Massis of Lofty Asset Management requested rezoning to allow for construction of a two-story multifamily building.

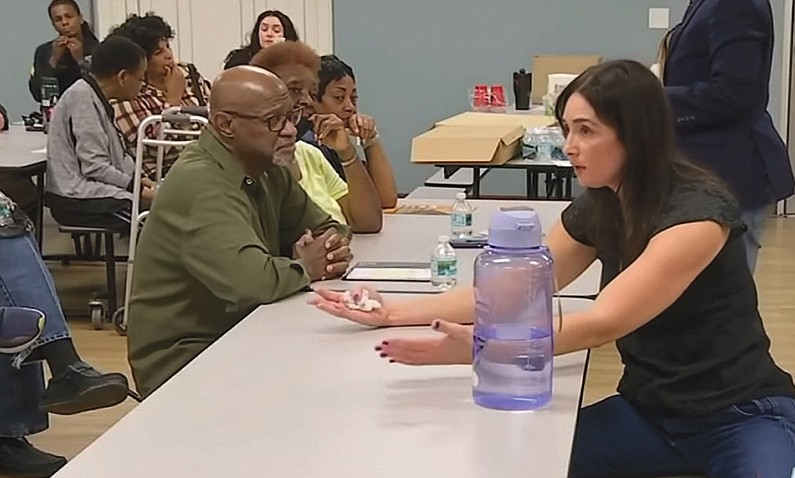

In hearings that together lasted five and a half hours, Council members heard complaints about the project from dozens of residents from the predominantly Black community surrounding the site. Speaker after speaker called the project unattractive and said it would bring crime and trash to the neighborhood while reducing their property values.

Massis, her team and her attorney, state Rep. Wyman Duggan, countered that the project would provide durable, sustainable and safe housing at below-market rates to working families in Northwest and North Jacksonville.

By the time the Council approved rezoning for the project on a split vote, the debate among board members had touched on racism and complaints that some Council members were deaf to the neighbors’ concerns.

“Yeah, I feel like this has become a Black-versus-white issue,” Council member Reggie Gaffney Jr. said.

At the base of the discussion were questions that Jacksonville increasingly faces as it grows.

With workforce and affordable housing in demand and developers buying property in or near established single-family neighborhoods to meet that demand, the questions included where those projects should be built, how much sway should nearby residents hold in the approval process and where a developer’s property rights end.

What wasn’t up for debate was Jacksonville’s need for affordable housing, which is prompting developers to seek properties for attainable housing in various parts of the metro area.

For any number of reasons a developer might be attracted to a parcel – its zoning, its affordability, its proximity to employers or schools and shopping districts – it’s not unusual for below-market housing projects to be proposed near single-family residences.

With those factors in place, and with the historic tendency of affordable housing projects drawing resistance from neighborhoods, it’s almost certain that the Biscayne Boulevard project won’t be the last to spark heated discussions in Jacksonville.

The need for affordable housing

According to an August 2023 report from Mayor Donna Deegan’s affordable housing subcommittee, 40% of Jacksonville households earn incomes below 80% of the area median income, the cutoff between low- and moderate-income housing.

Thirty-eight percent of households, or 147,200 total, were on the Jacksonville Housing Authority’s waiting list for subsidized housing, and the report cited an estimate that Jacksonville is short more than 35,000 units of attainable housing.

Meanwhile, the median home sale price across the Jacksonville metro area’s five counties was $389,000 in February, and the national average interest rate of a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage was about 7%, pushing the cost of home ownership out of reach for many households.

The rental market also produces challenges in affordability.

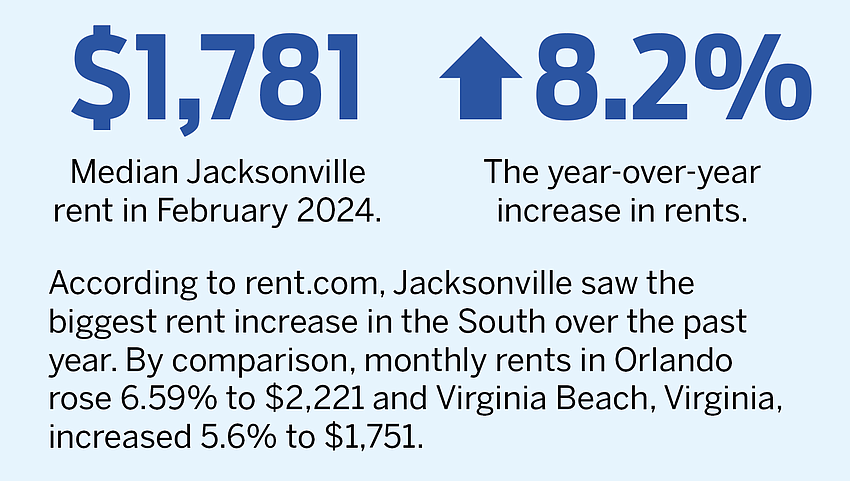

As reported March 25 by Daily Record news partner Jacksonville Today, a study by rent.com showed that Jacksonville experienced the sixth-largest increase in rent in the past year among 50 cities across the U.S.

The study said rent increased 8.2% in Jacksonville to a median of $1,781 per month.

A report last year by Florida Atlantic University and two other schools showed that a Jacksonville family would need to earn almost $71,000 to comfortably afford the area’s average rent, which at that time was about $1,750. The median household income at that time was about $58,000.

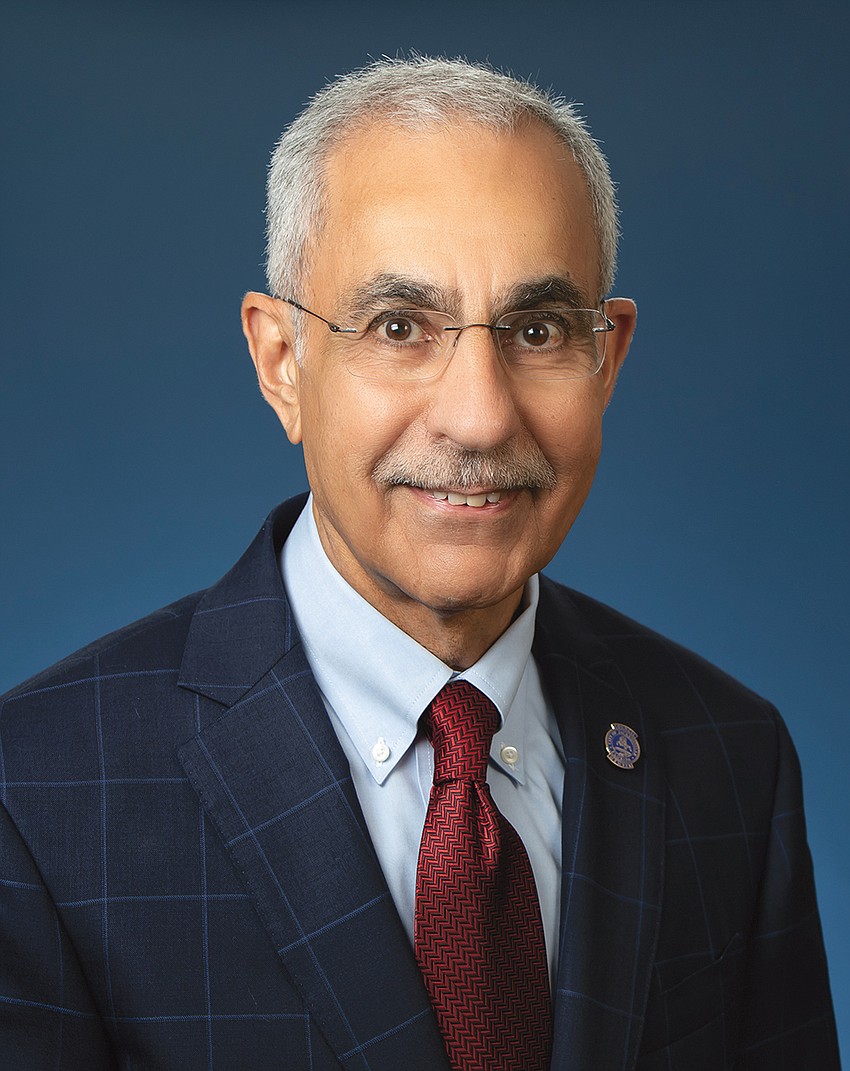

Council member Joe Carlucci, who chairs the Council Special Committee on Homelessness and Affordable Housing, said demand for lower-cost housing was driving developers to explore affordable housing projects wherever they might pencil out. He says another leading factor are state tax credits of as much as 9% for the development of affordable or workforce housing.

Political winds also are pushing for increased development of affordable housing. Deegan made support for medium- and low-income housing a part of her campaign platform.

In December, the Council approved $26 million in transition initiatives from Deegan’s administration, including a $1 million distribution to nonprofit organizations to help provide attainable housing.

Council is launching initiatives developed by the special committee led by Carlucci. Those could include more inclusive zoning rules.

Carlucci says he also is interested in condemning dilapidated, vacant properties and buying the parcels for development of affordable housing. The purchases would be made under the Jacksonville Community Land Trust, which was created in 2022 to buy and hold properties to ensure they remain affordable.

During a recent presentation at the Cuppa Jax series of community conversations, Carlucci urged audience members not to jump to conclusions about affordable housing projects.

“A lot of times you’ll hear ‘affordable housing,’ and you’ll think HUD housing or Section 8 housing. Those are almost not even included when people talk about affordable housing now. They’re a separate category, for the most part,” he said.

Carlucci said the definition of “affordable housing” today includes projects for people making $50,000 to $60,000 a year in stable, long-term jobs. In Jacksonville, affordable housing projects have included units for individuals making as little as 30% of the median income in the metro area. According to the city government website, the median household income for regional families is $70,533, of which 30% is $21,159.

The term workforce housing generally applies to people making 80% to 120% of the median income, with tenants unlikely to need subsidies to afford rent.

In Jacksonville, that would include incomes of $56,426 to $84,639.

Other terminology includes attainable housing, which generally applies to housing for which subsidies are not needed.

‘We need this type of housing’

During the debate on the Lofty development on Biscayne Boulevard, Council President Ron Salem recounted being “run over” by his colleagues in a November 2022 vote on the Madison Palms 240-unit affordable apartment community.

Salem opposed a rezoning request for the project, at Merrill Road and Interstate 295 near Salem’s home in Arlington.

Arguing against the rezoning, he pointed to an error in a Planning and Development Department staff report that said traffic on that segment of Merrill Road was at 63.7% capacity when it was actually at 123%.

Council voted 14-3, with Salem opposed, to rezone the property.

“We have got to place these things in everybody’s district – the Beach, Mandarin Southside, all over the place,” he said during the Council debate Feb. 13.

“I took mine. I took mine on the chin. But I’m going to vote for this (the Biscayne development) because I think this is what we need. We’ve heard it through our committees. We need this type of housing. And I took it in Arlington and we need to take it all over the place.”

Groundbreaking took place March 5 on Madison Palms, which will provide units to be leased to households at mixed income levels. Developer Vestcor has set the starting tier at 33% of the median income, $19,000 for a single individual and $27,000 for a four-person family.

During the same debate, District 6 Council member Michael Boylan compared opposition to the Lofty project to blowback among constituents in his district to a town home development planned amid single-family neighborhoods in Mandarin.

He said that while he sympathized with the Biscayne Boulevard neighbors about the design of the Lofty apartments, he didn’t like the design of the Mandarin town homes either.

“But we have to recognize that every one of our communities have to begin to embrace” workforce and affordable housing, he said.

“We need that kind of missing middle-income housing in all of our neighborhoods. And so I’m going to support this in principle, because I think it’s necessary for us to recognize the fact that we’ve got to make those voices that aren’t in the room here heard. Those who are looking for homes or looking for a place to live, we need to speak for them as well.”

Affordable housing also has spurred neighborhood backlash in northern St. Johns County, where the 288-unit Preserve at Wards Creek has drawn concerns over its impact on school capacity, roads and quality of life.

Not all affordable housing developments cause a stir.

An example is the $26 million Lofts at Cathedral, which will reserve some of its 120 units for tenants earning up to 30%, 60% and 80% of the area median income.

Jacksonville-based Vestcor, which reported in March that the project was 70% complete, also will offer market-rate units at the property. It is at 325 and 327 E. Duval St. Downtown, where plans for it drew little opposition.

‘I’m taking notes’

In the Biscayne Boulevard debate, no one – not even the project’s harshest critics – questioned the need for middle- to low-income housing in Jacksonville.

But neighbors said their area was already saturated with it.

Comparing the construction style of the Lofty project to a 1960s-era Howard Johnson’s hotel, they said it would bring crime, trash and a reduction in property values to the predominantly Black neighborhood surrounding it.

Speakers likened a rendering of the project to a “no-tell motel” and a prison facility, imploring Council members not to approve it unless they would allow similar construction in their districts.

Massis, the developer, said the steel-framed building was designed to last and to be secure, with an access-controlled perimeter gate and smart-tech locks on the doors of each unit. She said her goal was to build a property she could pass down through generations of her family.

The building includes a metal roof and siding, wood cabinetry, spray foam insulation, wood cabinetry and concrete finish flooring. She’s seeking to build two similar projects elsewhere in Duval County. Lofty plans to rent the units for $1,000 to $1,500 per month.

“It’s just a different way of building. It does look a little bit different. I’m proud of it. I hope to put it in all of your districts,” Massis told the Council.

She said she chose the site partly because of its proximity to workplaces such as the Mercedes-Benz operations center on International Parkway and the Amazon distribution center on Pecan Park Road.

Some Council members, including Raul Arias, defended Massis’ property rights and encouraged neighbors to consider that the apartment building would be operated by a local company as opposed to an out-of-town investor who may or may not be interested in maintaining it well.

“If you look at Lofty’s assets portfolio, you will see numerous properties that they manage which, to my assessment of what I’ve seen, have been properly managed, well-manicured, well-painted and the trash has been collected,” Arias said.

Other properties managed by Lofty include Topaz Oaks Apartments at 45160 Ewing Park Road in Callahan; The One @ Mandarin, 4295 Sunbeam Road; and The Square at 59 Caroline, 5959 Fort Caroline Road, in Arlington.

Council member Tyrona Clark-Murray, who voted against the rezoning, said the project echoed racist policies in Jacksonville’s history.

“This city has a habit since the 1960s of taking affordable housing and plopping it in the middle of middle- to high-income African American housing. And we have to stop. We have enough affordable housing along Biscayne Boulevard, and we don’t need any more.”

Gaffney urged Massis to work with community members on the aesthetics of the building and attempted to defer the vote. After failing on both fronts, he expressed disappointment and frustration.

“Thank you for diminishing and deflating the morale of District 8, of Biscayne, because that’s what you did,” said Gaffney, who represents the district.

He later referenced a saying, “Ain’t no fun when the rabbit has the gun,” suggesting the tables could turn and his Council colleagues could someday need his vote on a project opposed by constituents in their district.

“I have another issue in a couple of weeks and have the same exact issues,” he said. “And it’s going be interesting to see how you all vote. I’m taking notes.”

The debate took place during the Feb. 7 Land Use and Zoning Committee meeting and the Feb. 13 Council meeting, with the final Council vote 11-8 in favor of the project. The no votes came from Gaffney, Clark-Murray and Council members Ken Amaro, Matt Carlucci, Ju’Coby Pittman, Mike Gay, Rahman Johnson and Jimmy Peluso.

The vote didn’t put the friction over affordable housing to rest.

In the coming weeks, Council and the Downtown Development Review Board are expected to consider another project that is likely to draw heavy neighborhood opposition and contains an affordable housing element.

This one is a revised version of a Downtown Southbank mixed-use project with self-storage as its main purpose. After a tie vote by the Council in mid-2023, the developers are returning with a larger project that includes retail and apartment units dedicated to below-market housing.

Anticipating a large turnout of concerned residents, Joe Carlucci has asked the DDRB to ensure that a hearing on the project is held before the full board with no absences, even if that means scheduling a special hearing.