Retired Air Force Col. and astronaut David Scott became the fifth recipient of the Jacksonville University Presidential Global Citizen Award at a Feb. 28 ceremony at JU’s Arlington campus.

The award is presented to an “extraordinary, visionary leader whose impact is felt well beyond the bounds of their recognized responsibilities” and to an individual who “fully embodies the University’s ideal of a globally engaged citizen, bringing to bear their exceptional talents to create new opportunities to lead, live, and learn,” states the award’s page at ju.edu.

“Our focus throughout 2023 is on exploration and the art of the possible. Today, we recognize man kind’s passion to explore,” said JU President Tim Cost.

Cost interviewed Scott at the event.

Among his other accomplishments, Scott, 90, was the first man to drive the lunar rover on the moon.

Born to be a pilot

Scott was born June 6, 1932, at Randolph Field in San Antonio, Texas. His father, Tom Scott, was a U.S. Army Air Corps pilot who rose to the rank of brigadier general.

“When I was four years old, I decided I wanted to fly,” Scott said.

He received a bachelor’s degree from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1954, standing fifth in a class of 633.

Scott was commissioned in the Air Force and later graduated from the Experimental Test Pilot School and Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

In 1962, Scott received a master’s degree in aeronautics/astronautics engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

He was assigned to Air Force Test Pilot School in July 1962. Chuck Yeager, the first person to break the sound barrier, was commandant of the school.

After graduating as the top pilot in his class, Scott was selected for the Aerospace Research Pilot School, where test pilots who intended to become Air Force astronauts were trained.

NASA selected him as an astronaut in 1963 and Scott logged his first flight into space in March 1966 on the Gemini 8 mission.

Scott and Neil Armstrong spent about 11 hours in low Earth orbit. The mission ended prematurely after a malfunction caused the two-man spacecraft to spin out of control before Armstrong could stabilize it.

Scott then spent 10 days in Earth’s orbit in March 1969 when he was command module pilot of Apollo 9.

He made his third and final flight into space as commander of the 12-day Apollo 15 mission in July 1971, the fourth crewed lunar landing.

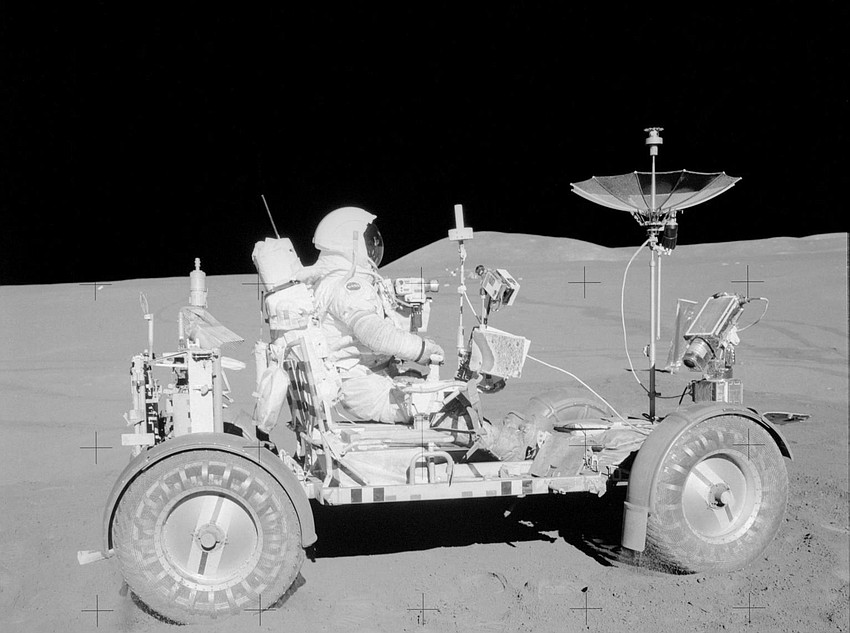

Scott and lunar module pilot James Irwin spent three days on the moon and were the first astronauts to travel across the surface in the Lunar Roving Vehicle – the battery-powered vehicle.

Scott said the rover weighed 180 pounds on Earth but just 30 pounds on the moon with one-sixth of Earth’s gravity.

“It was a marvelous machine – easy to drive and it gave us a 6-kilometer radius around the lunar module. We could pick it up if it got stuck,” Scott said.

Trained as a pilot and engineer, Scott said his assignment to Apollo 15 meant he had to embrace a new field of study.

“The mission focus was field geology. I had a great teacher – Leon Silver from Cal Tech. Geology is completely different from engineering, but pretty soon, I got the bug. When I got to the moon, I couldn’t wait to get out there and look at the rocks,” Scott said.

Silver was the W.M. Keck Foundation Professor for Resource Geology, Emeritus, at the California Institute of Technology.

On the engineering side of the mission, Scott said his and Irwin’s backpacks had emergency oxygen supplies that would allow them to walk back to the lunar module if the rover broke down.

If the rover was functional, the system was designed to allow both astronauts to have enough oxygen to share if one of the backup tanks failed, allowing both to ride back to the module.

If both backups failed, “well, then you had a bad day,” Scott said.

The highlight of the mission was the discovery and return to Earth of what came to be called the “Genesis Rock,” Scott said.

It is theorized that soon after the Earth was formed 4.5 billion years ago, another celestial body collided with the new planet and the debris slung into space coalesced and formed the moon.

Scott said the early crust of the moon was buried by volcanic activity, hiding the original primeval material under a layer of dust.

Scott and Irwin found a piece of the original crust and collected it to be returned to Earth for scientists to study.

“It was sitting on a pedestal, like somebody put it there for us,” Scott said.

Scott was the commander of Apollo 15. Irwin was the lunar module pilot and Alfred Worden was the command module pilot of the July 26-Aug. 7, 1971, mission.

Cost noted that Scott is “the only living person out of 8 billion of us in the world who was a commander of an Apollo mission.”

A distinguished career

Scott retired from the Air Force in 1975 with the rank of colonel. He logged more than 5,600 hours of flying time, including nearly 555 hours in space.

“I took the right path and ended up at the right place at the right time,” Scott said of his career as a test pilot and astronaut.

The global citizen award is the latest on Scott’s resume.

He received two NASA Distinguished Service Medals, the NASA Exceptional Service Medal, two Air Force Distinguished Service Medals and the Air Force Distinguished Flying Cross.

Scott received the Air Force Association’s David C. Schilling Trophy, awarded for the most outstanding contribution in the field of flight in the atmosphere or space by an Air Force military member, Air Force civilian, unit or group of individuals; and after Apollo 15 the Robert J. Collier Trophy, awarded to recognize the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics in America, with respect to improving the performance, efficiency and safety of air or space vehicles.

He is a member of the International Science Hall of Fame and the Astronaut Hall of Fame.

Scott and his wife, Mag Black Scott, are Northeast Florida residents and JU benefactors.

He supports the revival of manned space exploration.

“Hopefully, we will get back to an Apollo concept and let this generation get out and play in the sand,” he said.