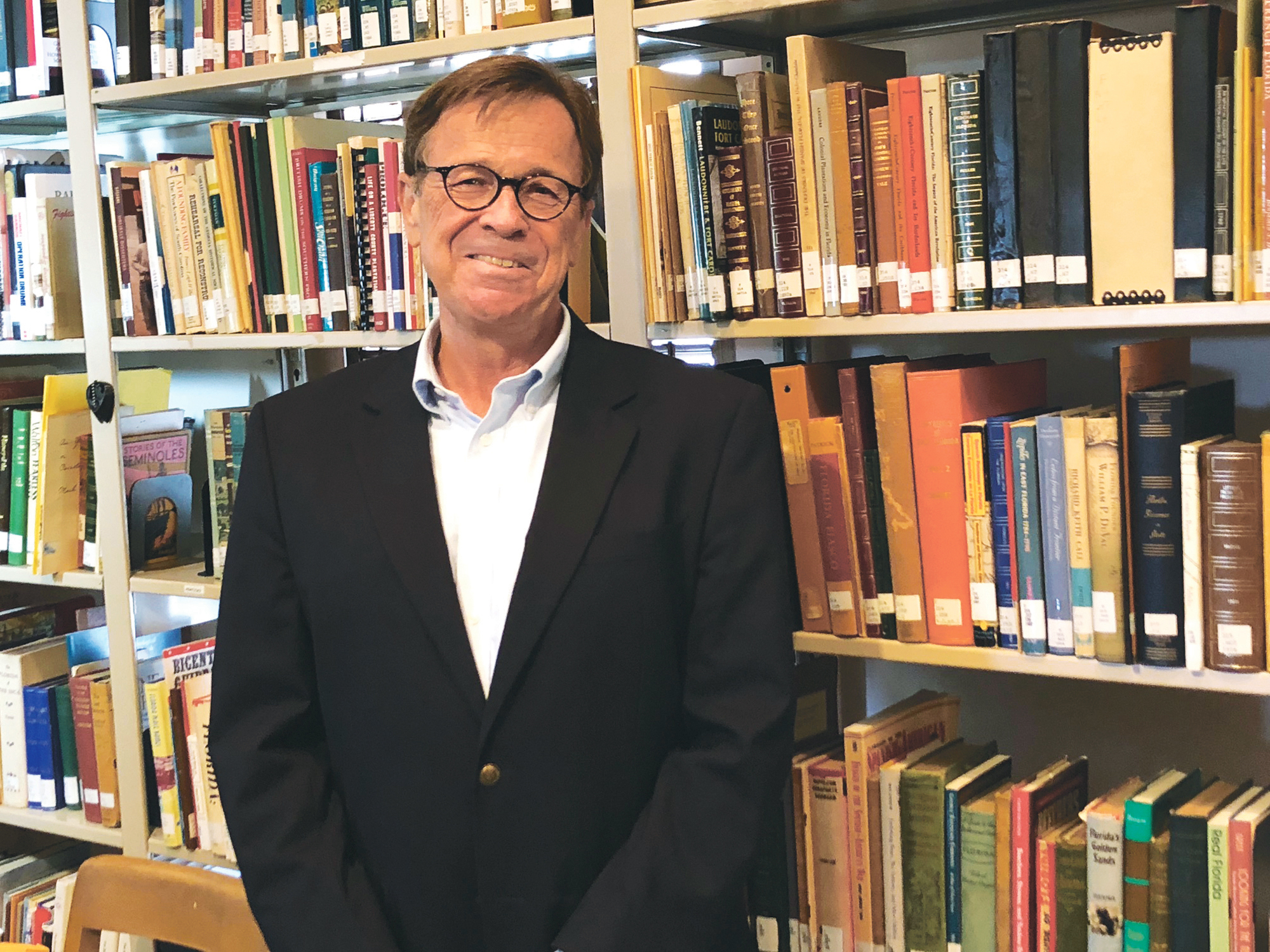

By Alan Bliss, Executive Director, Jacksonville Historical Society

Today, after 50 years of city-county consolidation, Jacksonville’s distinctive form of government remains a work in progress.

It defines the city, differentiating it from nearly every other American urban structure.

Some of the problems its authors sought to resolve have indeed given way, while others persist.

All by itself, consolidated local government is accountable neither for its successes nor its unmet promises. Jacksonville’s elected officials — and the voters who choose them — are ultimately responsible.

Consolidation put new tools in the hands of elected officials, and the effects on Jacksonville’s business community often parallel those felt by citizens.

A thought since 1929

By 1968, thoughts of consolidating the City of Jacksonville and Duval County into one government had circulated for decades.

In 1929, Jacksonville’s first city planner, George W. Simons Jr., recommended that the city coordinate with the county on such things as street plans and zoning ordinances to avoid conflicts at the boundary between the two jurisdictions.

In 1935, at the request of the county delegation, the Florida Legislature adopted a statute enabling consolidation in Duval County, if the voters approved.

Cities elsewhere in Florida, especially Tampa and Miami, explored the consolidated government idea after failed attempts at annexations.

Both were fast-growing counties surrounding declining residential neighborhoods and central business districts.

Born of dysfunction

By the 1960s, Jacksonville resembled other American cities that faced aging infrastructure and dysfunctional government.

Residents and businesses increasingly relocated, leaving behind urban problems in favor of increasingly remote suburbs.

Downtown Jacksonville suffered visibly, with a declining tax base no longer adequate to sustain municipal services.

The interests of civic elites were divided between the traditional urban core, where businesses typically existed, and the suburbs, where they owned homes and raised their families.

All of these disruptions came at a moment when cities like Jacksonville badly needed fresh resources with which to modernize and adapt to a changing economy.

Duval votes for change

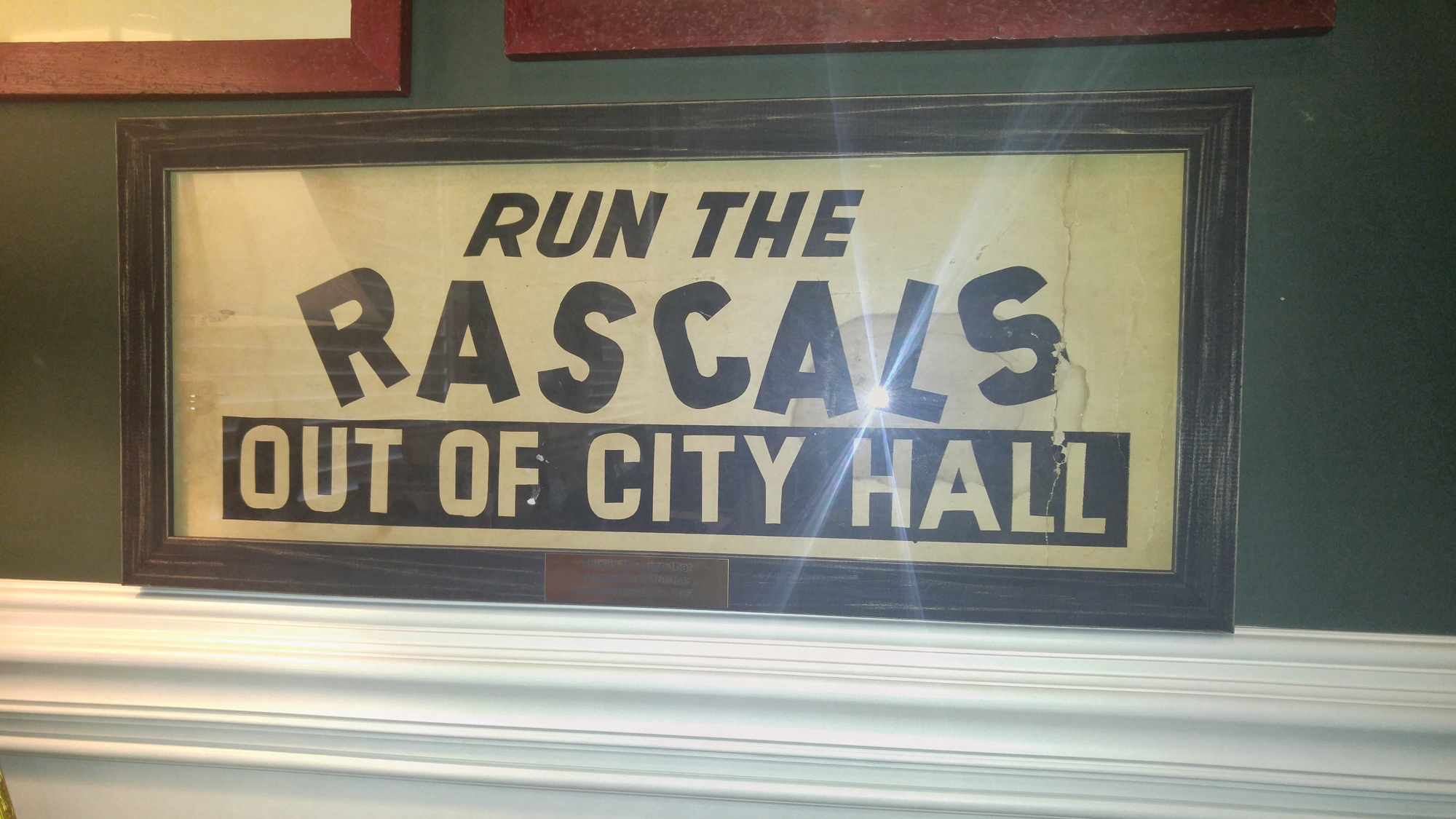

Jacksonville’s situation was complicated by the dominance of an enfeebled and, in some cases, corrupt political regime.

Elected commissioners individually controlled the departments of government, such as streets, police and fire, electricity, and so on. Some became the personal fiefdoms of their powerful administrators.

Meanwhile, Duval County’s government operated independently, with limited resources to provide public services to a population that was rapidly expanding outside the city limits.

In the mid-1960s, at the time of Jacksonville’s consolidation campaign, the cities of Tampa and Miami also sought to consolidate with their county governments.

In both cases, voters rejected the change, while Duval’s voters approved.

Why consolidation campaigns failed elsewhere while succeeding in Jacksonville is a question that fascinates students of urban politics.

Unified services yield efficiencies

One result of consolidation was that local fire and rescue services became unified, achieving greater financial efficiencies as well as delivering more uniform and responsive service to business and residents across the entire county.

Fire insurance underwriters recognized the improvements, and premiums declined.

In other parts of Florida, such benefits took decades to achieve, coming only after contentious struggles to adopt countywide fire-rescue departments.

Unified law enforcement also resulted from consolidation, creating efficiencies of scale that other urban police agencies lacked.

In addition to fostering efficiency, consolidating the functions of government stimulated professionalism.

Larger city departments meant the stakes for success or failure were high, which drew greater scrutiny of their performance.

Demand increased for administrators with talent and credentials. Placing city departments into the hands of professional managers, rather than elected commissioners, helped level the field among companies and individuals seeking to do business with the city.

The city’s electric department became part of a more independent governmental agency, the Jacksonville Electric Authority, which subsequently took over water and sewer utilities as well and is known as JEA.

The Jacksonville Transportation Authority came into existence somewhat differently, as the successor to a state-chartered agency called the Jacksonville Expressway Authority.

JTA benefited from the legacy of the Expressway Authority by inheriting a pioneering network of limited-access roads and bridges, funded by tolls. The revenue created endowed the JTA with a source of finance that helped stabilize its early years.

Transportation infrastructure, a perennial challenge for other Florida counties, benefited from an organized and coherent planning and construction process.

Softening the urban-suburban divide

In civic affairs, consolidation helped soften the urban-suburban divide that rose out of the urban crisis of the 1960s.

American cities in the 1960s experienced the culmination of events that had been accelerating since 1950 – arguably the high-water mark of downtown central business districts.

New technologies, increasing auto ownership, white flight and industrial change stimulated suburban expansion.

What we now consider desirable historic neighborhoods were then decayed and blighted.

With consolidation, influential leaders in Jacksonville, who previously may have lived in suburbs outside the city, were suddenly back within the city limits.

A more coherent metropolitan identity took hold, reinforcing perceptions of Jacksonville as a valuable market area. Among other things, the potential strengthened the business case for an NFL franchise, which Jacksonville won in 1993, with the Jaguars beginning play in 1995.

The benefits to Jacksonville’s brand spread across Northeast Florida and beyond.

Some believe that without consolidation there would have been no NFL franchise.

Market coherence presents challenges

Jacksonville’s market coherence only goes so far, though.

In electoral politics, for example, the city is rambling and complicated.

Campaigning for a citywide office, such as that of the mayor, requires an advertising budget sufficient to reach hundreds of thousands of citizens.

Some members of City Council are elected citywide at large, but others often are little known outside of their home districts.

Jacksonville’s voters occupy precincts that range from rural to urban, beaches to farmland, with problems and issues that often are highly local.

Those contrasts also are challenging to the Jacksonville sheriff, an elected position responsible for widely varying police jurisdictions.

Taking stock

Municipal governance can seem abstract.

To Jacksonville’s citizens and visitors alike, how the city works matters less than the fact that it works at all.

And yet, the way that Jacksonville reorganized itself 50 years ago, as a constellation of neighborhoods, is one of its defining characteristics, setting it apart from most American cities.

In the 21st century, its people have inherited problems that afflict many urban places.

Consolidated government is no magic bullet. What it offers is a way toward solutions that call on a sense of citizenship and belonging to a large and diverse community.

Today is a moment to take stock of its results, and to take heart that it can accomplish much more, if we want it to.

The first City Council of Jacksonville’s consolidated government. Top row from left, Jack Carter, Jake Godbold, Walter Dickinson, Sallye B. Mathis, Mayor Hans Tanzler, John Lanahan, Mary Singleton, I.M. Sulzbacher, Homer Humphrey, Earl M. Johnson and W.E. “Ted” Grissett. Bottom row from left, Don MacLean, Wallace Covington, Johnny Sanders, Joe Carlucci, Oscar Taylor, Earl Huntley, Bobby Moore and Walter Williams.