Sean Shaw remembers visiting his father’s office in Tallahassee after school and on the weekends.

He’d wear his backpack into the stately building that had a half-dozen white columns out front.

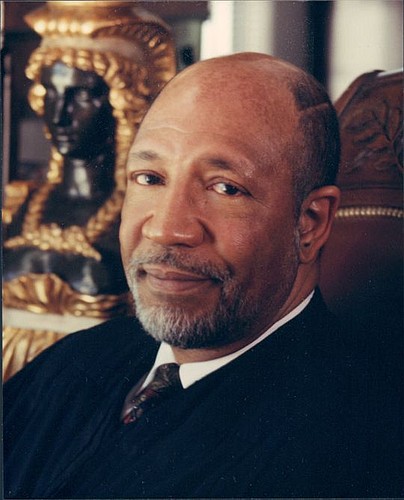

He’d go through security where the guards knew he was the son of Florida Supreme Court Justice Leander Shaw Jr.

And when he needed “play paper,” the younger Shaw used Supreme Court briefs.

“As a kid, you don’t know it’s a big deal,” Shaw said of his father’s job or his stature in the legal community.

The elder Shaw was just a dad who taught his children to fish, keep their grades up and do what’s right.

Others, though, knew the father of five was a big deal.

A pioneer as one of a handful of African-American lawyers practicing in Jacksonville in the 1960s.

A legal giant as the second black Supreme Court justice and the first to serve as its chief.

Shaw was a man who was as comfortable debating a momentous Supreme Court case as he was telling a story on the porch at his American Beach home. He was persuasive at both.

In law school, Sean Shaw began to learn what a big deal his father was.

And the family has heard countless reminders since the 85-year-old retired justice’s passing last week.

Trailblazer from the start of his career

When Henry Adams started practicing law in 1969, he met Shaw through the D.W. Perkins Bar Association.

Adams described the fledgling association as “basically a group of seven or eight black lawyers in Jacksonville who got together every month and commiserated with each other.”

That was the same year Shaw was hired by State Attorney Ed Austin and eventually led the office’s Capital Crimes Division.

For a black lawyer to hold that job at that time was remarkable, said Adams, now a U.S. District senior judge.

Former Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice Major Harding recalled a memorable case when he was a Duval County juvenile court judge in the late 1960s.

He said Shaw represented a grandfather trying to get custody of his grandchild after the mother jumped off a Downtown bridge to commit suicide. A grandmother also was trying to get custody of the child.

Harding said it was “very obvious” Shaw’s client should be awarded custody. Shortly after Harding left the courtroom, the grandmother pulled a gun.

“It was quite an issue,” said Harding, who will eulogize his friend Tuesday.

Harding said Shaw was “solid and clear” as a lawyer, one who “represented his clients well.”

One of those clients was U.S. District Judge Brian Davis who, as a college student, hired Shaw to represent him in the 1970s. He was impressed with Shaw’s stature, demeanor and professionalism.

Shaw became a role model Davis would watch and admire the next few decades. He said he has used, and will continue to use, Shaw’s writings as guides in developing his own body of legal decisions.

Though Harding and Shaw became friends in the late 1960s, the two actually shared a milestone that was unknown for three decades.

Both were sworn in to The Florida Bar the same day in June 1960. More than 30 years later, Harding discovered he and Shaw were standing next to each other in the photo taken that day on the steps of the Florida Supreme Court.

“To think, years later he and I sat on the same court,” Harding said last week.

And for a couple of years, they sat next to one another. Practically bookending their careers shoulder-to-shoulder.

Becoming a justice

After a series of corruption scandals in the 1970s, Supreme Court elections were eliminated and justices would instead be appointed.

Former Gov. Bob Graham had the first appointment in 1983 and chose Shaw, someone with whom he was familiar.

Four years earlier, Graham had selected Shaw to serve on the 1st District Court of Appeal.

It made it easier for Graham to choose Shaw from the candidates for the Supreme Court post.

“That was an appointment in which I had a great deal of confidence,” said Graham, who was governor from 1979-87.

Shaw served 20 years on the Supreme Court, including as its chief justice from 1990-92.

During that time, the court decided landmark cases such as authorizing a recount in the 2000 presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore.

The decision was the focus of the HBO movie, “Recount,” in which local attorney Craig Gibbs played Shaw in the movie.

When Gibbs was contacted by the movie’s casting director, he thought it was a hoax. When he realized it wasn’t, he wanted to get Shaw’s permission to play the role.

“Craig, I’d be delighted,” the justice replied when Gibbs asked for his permission.

It was the last time the two men spoke.

Shaw also was a staunch opponent of the electric chair, at one point comparing it to the guillotine.

He sent three graphic photographs from a Florida execution to the U.S. Supreme Court in his dissenting opinion of the state’s Supreme Court’s 4-3 decision to continue using the electric chair.

While most Florida Supreme Court justices face little opposition during retention elections, Shaw faced a strong push after authoring a 1989 opinion striking down the parental-consent requirement for minors seeking an abortion.

The justice said at the time the decision was based on a privacy right from the Florida Constitution.

His son, Sean, remembers that time well. The days he’d go to the family’s mailbox and find photographs of fetuses. And seeing the bright yellow fliers with a check mark in a “no” box, encouraging people to vote against retaining his father.

Love of fishing and sharing stories

The bulk of Shaw’s memories of his father are more personal, though. Many center around the justice’s love for fishing and the competitive spirit that often accompanied it.

When Shaw got one of his first paychecks, he bought a bunch of fishing tackle his father didn’t have. When the two went fishing again, the son got far more bites than the father.

“What are you fishing with?” Shaw remembered his father asking.

The next time the two went fishing, Shaw’s father had not only purchased the same tackle his son had used before — he had bought even more.

Justice Shaw also enjoyed fishing and spending time at his home in American Beach.

In what was likely the most powerful corner in the area, Shaw had two judges who were neighbors. Adams lived next door and Davis had a place across the street.

Both judges enjoyed their time with Shaw during his visits to American Beach, which dwindled as his health began to fail.

Adams said he and Shaw — who both graduated from Howard University School of Law — would sit on the porch, drink a Diet Coke and talk about family, friends or what lawyers around the state were doing.

One topic was off limits, though, Adams said: “He wouldn’t talk about his cases and I wouldn’t talk about my cases.”

Davis said he and Shaw sat on that same porch on many occasions and “talked about solving the problems of the world.”

He said Shaw had a “delightful sense of humor” that he enjoyed very much.

The two also shared a love for fishing, particularly surf fishing, and would often meet at daybreak. Shaw taught Davis he could catch a fish almost at arm’s length with the right bait and the right spot.

Adams said Shaw was still the same man he knew when he first started practicing four decades earlier. “He didn’t walk on the clouds,” Adams said. “He put his britches on the same way every morning.”

That humbleness was among the many qualities his friends and colleagues admired.

Harding also appreciated Shaw’s sense of humor. “We had a lot of laughs together,” he said. “Those are special memories that I cherish.”

Graham said Shaw had a well-earned reputation of being a good storyteller.

“If you saw Leander coming, you wanted to steer over to steal some time with him,” Graham said.

Shaw’s death is a major loss in the community. A monumental one, in fact, Davis said.

“I’m at a loss to identify a citizen in recent history whose passing meant this much to this community,” Davis said.

The loss of a legend

For the Shaw family, the loss is unmatchable.

The justice had enjoyed the bulk of his retirement years, particularly not having to wear a suit every day, Sean Shaw said.

“I bet I could count on two hands the number of times he wore a suit after his retirement,” Shaw said.

For most of the years after leaving the court, the retired justice had no major health problems. “He was as spry as ever,” Shaw said.

When the elder Shaw had a stroke in October 2014, his motor skills were fine and he was still able to fish.

A few months later, he had a second stroke that was much more debilitating.

Shaw said the last time he and his father went fishing was in the summer of 2014.

He’s not sure what it will be like the first time he goes after his father’s passing. “It will be tough,” said Shaw, the youngest of the justice’s children.

Even tougher will be, once he and his wife have children, figuring out how to describe their grandfather.

“I’m probably not even ready to answer that question,” he said.

Not ready to figure out how to let them know what a big deal their grandfather was.

@editormarilyn

(904) 356-2466