The topic hasn’t reached the level of water-cooler conversation yet, but proposed government regulation of greenhouse gas emissions from electric power plants is a subject that will impact, in some way, every person and business in the U.S.

On the local level, Mike Brost, JEA vice president and general manager of electric systems, said at the public utility’s June board meeting that a new set of proposed carbon dioxide regulations represent “one of our top corporate risk items.” He predicted any new regulations are sure to impact JEA’s bottom line.

“There is a higher cost of business in our future,” said Brost.

On June 2, the Environmental Protection Agency released proposed guidelines, the “Clean Power Plan,” for carbon dioxide emissions produced by existing plants that use fossil fuels to generate electricity. The proposed standard would reduce carbon dioxide emission from the power sector by 30 percent nationwide before the 2030 deadline for compliance.

In terms of percentage reduction in carbon emissions compared to 2012 levels by state, North Dakota at 11 percent has the smallest required reduction, while the largest reduction would have to be achieved by Washington at 72 percent. Florida’s required reduction is listed at 38 percent, according to the proposed Clean Power Plan.

Bud Para, JEA chief public affairs officer, said the solution to reduce carbon emissions from power plants is to drastically reduce — or even eliminate — the use of coal to generate electricity.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, last year, 62 percent of Florida’s electricity generation was from natural gas, 21 percent from coal and 12 percent generated by nuclear power plants. Other resources, including renewable energy, supplied the remaining 5 percent.

Para said in 2013, 65 percent of the electricity generated by JEA came from coal. In 2012, only 35 percent was generated by burning coal due to a drastic drop in the price of natural gas that year.

Generating more electricity with natural gas than with coal is one of the four “building blocks” suggested by EPA to be used by states to develop their carbon reduction strategy. Natural gas produces half the carbon emissions compared to coal, said Para.

Improving the efficiency of existing coal-fired units is another suggested strategy — generating more electricity with the same amount of coal.

Using generating sources that do not produce carbon emissions also is a suggested strategy. Para said in JEA’s case, that means adding more nuclear power into the mix.

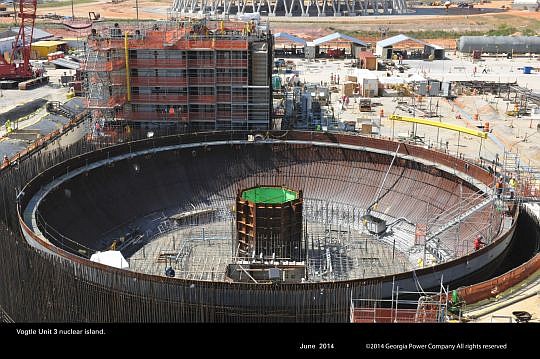

An expansion of Georgia Power’s Plant Vogtle in Waynesboro, Ga., is scheduled to go online in 2017. JEA has a 20-year contract to purchase electricity from the expanded plant. The amount of electricity JEA plans to purchase from the plant will increase nuclear to 10 percent of JEA’s inventory.

Para said JEA also has an option with Duke Power to purchase part of a plant that is in the licensing and permitting phase. Assuming the new Duke facility goes online, that could increase the share of electricity generated by nuclear energy to 20 percent of JEA’s total.

“It certainly will be a big part” of JEA’s future energy distribution, said Para.

It’s likely to be a long debate, since the ultimate scope of the standard won’t be known for another year, said Para.

Utilities and other parties interested in the new regulations, including environmental advocacy groups, have 120 days from the official filing of the EPA’s proposal to comment. The final form of the regulations won’t be enacted until June. Then, Florida won’t have to file the state plan to meet the standards until June 2016.

Para said he expects lawsuits will be filed in 2015 soon after the final regulations are announced. Utility companies will likely question EPA’s jurisdiction and environmental groups are likely to contend contend the regulations aren’t strict enough.

The final cost to utilities, including JEA, to conform to the new regulations can’t be accurately estimated until the regulations are finalized.

Para said considering the goals for carbon emissions from power plants won’t have to be fully met until 2030, it’s likely new technology could be developed that could reduce emissions using methods not even imagined at present.

New ideas and processes could come from independent inventors or from companies with established research and development departments.

“There is a lot of money involved. It will encourage people in their garages and General Electric and duPont will work on this,” he said.

@DRMaxDowntown

(904) 356-2466