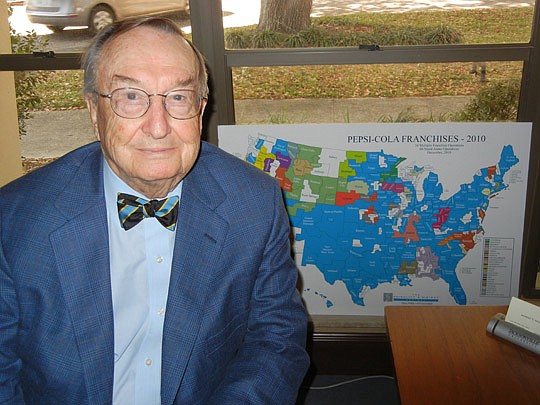

Bob Shircliff is a well-known name in town.

Shircliff supports very well-known causes, including St. Vincent's HealthCare, The Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, the Jacksonville Symphony, Jacksonville University and the Catholic Diocese of St. Augustine.

In fact one of the streets at St. Vincent's in Riverside is called Shircliff Way.

Shircliff began his career in 1950 and worked his way up in his father's business from a bottler to the president of Pepsi-Cola Allied Bottlers.

He moved to Jacksonville in 1967 and later sold his bottling companies to General Cinema Corp. He then created Robert T. Shircliff and Associates, which several years later became The Shircliff Group.

Shircliff, 84, and his wife, Carol, remain very active in Jacksonville's philanthropic community.

The Daily Record interviewed Shircliff for "First Coast Success," a regular segment on the award-winning 89.9 FM flagship First Coast Connect program, hosted by Melissa Ross. The interview took place at the station at 100 Festival Park Ave. along the St. Johns River near EverBank Field.

The interview is scheduled for broadcast this morning and the replay will be at 8 p.m. on the WJCT Arts Channel or online at www.wjctondemand.org.

Following are edited excerpts from the full transcript.

Tell us about your early years. Where did you grow up and what were your goals?

I grew up in a small town, Vincennes, Indiana. Incidentally, Vincennes was 17,000 people in 1900 and it was 18,000 in 2000, so it hasn't gone very far very fast. But it is still a nice place to grow up. I went to school there and after the eighth grade I went to Culver Military Academy for four years. After Culver I went to Indiana University and graduated from IU in 1950. At IU I met my wife, Carol, and now we have been married for 60 years.

That's pretty good. That's a life story right there.

What did you want to be when you were growing up?

I know growing up I wanted to be a lot like my father. My father was such a good man. He grew up in a small town in Indiana. After he went to IU he was in World War I and when he came back from the war he met my mother and she lived in Vincennes, and he moved to Vincennes.

He was in the hardware business and then in a small chemical business and then in about 1930 he went into the basket business, weaving baskets for floral displays. Suddenly it became one of the largest floral display manufacturing companies in the country called Shircliff Industries.

But along came the Depression and by 1935-36 people weren't buying flowers and if they didn't buy flowers they didn't buy baskets and sometimes the florist sold the flowers and the baskets and didn't pay for the baskets, and my dad didn't like that very well.

One summer we were in Michigan on a vacation and he saw a Pepsi-Cola in the cooler at this service station where we were buying our gas. I came out with this Pepsi and I told him this great big bottle only cost a nickel. He couldn't get over it and lo and behold we were driving down the street, he saw a Pepsi-Cola bottling plant.

My father was always very curious so he went in to see the owner and he took me with him. He took me everywhere, and maybe that's why I wanted to be more like him.

He found out that they sold this soft drink for a nickel and he found out that the price was the same to everybody and that the retailers paid cash. He was still trying to collect for his baskets and here is a man in Detroit selling his stuff for cash.

They made a bond and they were friends and six months later my father was in the Pepsi-Cola business in Southern Indiana, selling Pepsi's great big bottles for a nickel and all the retailers were paying cash and the families lived happily ever after.

When did you join the business?

He went into the business in 1936. I was 8 years old and I started going to the business and then I started getting paid. When I was 14, I used to get a quarter an hour. That was good.

I did everything that a laborer does. I loaded sugar bags, I loaded lots of cases, I loaded trucks, I sorted bottles. I did all those things in the summers until I went to college. When I went to college I worked full time or part time in the Pepsi-Cola bottling company in Bloomington, Indiana, which was one of my father's other plants. I would go there after classes while I was in college and I would load the trucks and sweep the floors and I did a lot of mopping.

I did a lot of cleaning and I emptied waste-paper baskets and cleaned up the bottling room and I was getting $15 a week then. That was pretty good money in 1947-48. That helped me get the things I wanted in college that a lot of people didn't have. That 15 bucks extra was really good.

When I graduated I went to work for the Pepsi bottling plant and it was a great experience. In 1955 my father and I bought the Pepsi-Cola plant in Charleston, West Virginia, and Carol and I took our new daughter and moved there. The manager that had been in Charleston was 10-12 years older than I was and he was just an incredible human being and his name was Pat Vallandingham.

I went to Charleston representing ownership and Pat was working for us, but I was really working for him. I learned so much from Pat. He worked hard and he had the right skills and he was sort of a younger reflection of my father. Pat and I became close friends.

I've always been blessed because I have always liked what I'm doing.

Soft drinks are a moment of refreshment for people. You're selling a little bit of happiness in a busy world. You don't drink it when you're mad. You drink it when you feel like you want a moment free and you want to do something interesting or fun, and so you have a soft drink. We always tried to be there.

What brought you to Jacksonville?

My father and I liked acquiring bottling plants. In 1963 we purchased the Pepsi-Cola bottling plant in Lynchburg, Virginia. When I went down there to buy that plant, I heard that (the owner) had turned down a lot of buyers simply because he wanted to sell but he didn't have to sell and he didn't like the people that were trying to buy it. I thought, what chance do I have?

I went to Lynchburg. I drove down there and I said a lot of prayers on the way. I really did. I'll never forget it because I was going to meet the meanest man in the world.

I was just a kid and I didn't know what to expect. I went in there and when I told the secretary who I was, she called back to the owner and suddenly from the end of the hall I heard, 'Come back here, young man.'

I went back and sat down and told him what a wonderful man he was and how happy I was to be there and what a beautiful facility he had and how well run it must be and before long we were best friends and two days later, just two days later, we shook hands on a deal.

The remarkable thing is that I had accomplished then what no one else had been able to do and that was to buy this superb business for a price I thought we could afford.

When I called my father and told him that I just shaken hands on buying the Pepsi-Cola bottling plant in Lynchburg, Virginia, he said, 'Well, Bob, do we have any money?' I said, Dad we don't even have 10 percent of the purchase price in the bank, and he said, 'How are we going to pay for it?' and I said, you are going to have to help me borrow the money someplace.

My dad got on a train and we met in New York and talked to some banks there and they said we would like to loan you the money but we will have to participate with somebody. He and I flew to Chicago and we talked to a big bank in Chicago and they said it was the best presentation and the best transaction that they had ever seen, but they couldn't go the whole route.

I only had 30 days to raise the money. I couldn't do it today. Back then you did it on a handshake and trust and a good story.

At any rate, it was too big of a deal for the bank in Vincennes and too big for a bank in Charleston, West Virginia, so we went back to Lynchburg where they knew the business well and my father and I made a presentation to the bank in Lynchburg. They said it was the best presentation that they had ever seen.

They knew the business and they had checked on us and they learned that my father had done a lot of things in his life and he never missed a payment to anybody in his life, and that's what really did it.

They asked if we could come in on Saturday morning, which was about five days before the deadline, and we went and stayed in the town, went to the bank and they said, 'We don't want the bank in New York, we don't want the bank in Chicago, we don't want any other banks. We will loan you the whole money, you can have it tomorrow, Monday.'

That was a good deal. We paid that loan off in five years and stayed way ahead on schedule.

In the meantime, Jacksonville came up. That is why the Pepsi company wanted me to move to Jacksonville. I didn't mind moving to Jacksonville. We had looked around the city and this was a good place to be. It was a business community. It wasn't like the rest of Florida.

We had good weather and a nice city and nice welcoming people and nice bankers and good lawyers and all the things that a businessman would be looking for.

Mostly it looked like a good place to live. We ended up with the help of Pepsi-Cola buying this plant and the one in Gainesville and the one in Savannah. Then a couple of years later we sold them all to General Cinema, but we stayed in Jacksonville and didn't want to move to Boston. (I spent) five years with General Cinema, buying a lot of plants for them and consolidating their beverage business.

When I left, General Cinema was the largest independent soft drink bottler in the country.

That is when I started Robert T. Shircliff and Associates and consulting to bottlers. Since I had been president of the national Pepsi-Cola Bottlers Association a few years prior to that, I knew everybody in the country, fortunately for me. That was another blessing.

One month after opening my new consulting office I had six clients and then 25 years later with my good partners we ended up merging and selling about 90 percent of the Pepsi-Cola plants in the country.

It was a fun business, a hard business, hard work. I really enjoyed it. In my first plant in Bloomington that I was involved in full time, we turned out 60 bottles a minute. People used to stand in the front window and watch these 60 bottles a minute go past. The last bottling plant I was in about two years ago had two can lines running side by side and they were putting out 4,000 Pepsis a minute.

I have seen the industry go from 60 a minute to 4,000 a minute and consumption of 100 bottles per capita to 600 bottles per capita. It's just been a wonderful story for me and for my family.

I wouldn't do something that wasn't fun.

(In 1988, General Cinema Corp., one of the nation's biggest soft-drink bottlers, movie exhibitors and department-store operators, agreed to sell its soft-drink bottling business to PepsiCo Inc. for $1.5 billion.)

You have been supportive of the community. How did that come about?

We all reflect the people that we are associated with, the people that we grew up with, the people who are our friends. My father was always involved in his community. In Charleston, West Virginia, I was well tutored by my friend Pat. When I came to Jacksonville, I lived next door to Jack McCormack, who was one of the great people I have known in Jacksonville and my best friend.

Jack got me started in some things. My wife and I have never lived extravagantly. We have always had time and a little money and we have found the joy of giving. That really has been a big part of our lives. Do you know anyone that doesn't enjoy giving a gift? You know when you go shopping you enjoy it, to buy something for someone else. And when you give even a small gift to someone who really needs it, they are so grateful. To see how much good you can do with so little is part of the joy of living.

How do you choose the causes that you support?

It all goes back to example and faith. At St. Vincent's, for example, I see an opportunity to support programs that serve the poor. One of the very first things the sisters there, the Daughters of Charity, told me 40 years ago when I went on the board was, 'Look, we want the best health care for everybody. The poor people come in and get the same rooms as the well-to-do, and the well-to-do get the same rooms and the same nurses and the same care. We treat everybody.'

It goes back to the ancient tradition that says we save our best silver for the poor. You can just see and feel the good that a little help provides. That is what I have found so exciting about St. Vincent's.

It is also true at United Way. I like to see the quality of life through the Symphony and Cummer. I like JU. It is a private wonderful school and the business school there professes free enterprise in a really beautiful way and the graduates do very well. The new president of JU is a graduate and I had the honor of signing his diploma when he graduated because I, at that time, was chairman of the board. I've got a little piece of the action out there because I can always get that diploma back.

The Catholic schools are the same way. The Guardian of Dreams, we educate 400 kids a year. We change lives.

When you can change lives with a little bit of time and a little bit of money, that makes a happy day.

You have been in Jacksonville for 46 years and you are quite invested in the community. What would you like to see in Jacksonville?

When I was driving here to the studio, I came past the old shipyards. It looks better than it has in a long time. It is mowed and clean, but nothing's on it. For 40 years, we have been talking about a vibrant Downtown. Today we have vibrant suburbs, beautiful suburbs. We have the beaches, we have the Town Center, we have the Avenues, we have the Northside shopping center. We have all these things.

We haven't seen a vibrant Downtown. As I was driving by the old shipyard property, I thought, when are we ever going to get this issue solved? When are we going to bring people Downtown? There are developers in America who would love to have that property and it is owned by the City and we give incentives to people to come here and bring employment.

We have a valuable piece of property that ought to go to somebody who really wants to do something with that. If the Town Center and the people who developed the Northside (River City Marketplace) can take that space and make them the wonderful places they are, think what we could do with that acreage on the river.

I am going to talk to the mayor.

What else would you like to share?

I'm happy to be in Jacksonville. I'm 84 years old, happy to get up in the morning. I have a wonderful family, a wonderful life, nice friends and I hope I am here a whole lot longer.

@MathisKb

(904) 356-2466