In my previous column, I asked everyone to make room for the advancement of female lawyers.

Achieving equity isn’t just the job of firms and their diversity committees. It requires the cooperation of opposing counsel and the willingness of the bench to step in and force that cooperation when needed.

Summed up, when faced with choices, our profession should lean aggressively toward the option that encourages diversity of all kinds, particularly when the choice typically costs us so very little.

Recently, a friend emailed me a link to news coverage of Christen Luikart’s experience in Palm Beach County. Luikart, co-chair of the Jacksonville Bar Association’s diversity committee, a great lawyer and an all-around good person, is lead counsel on a matter pending in Palm Beach. The case was filed in 2016 and was on its first trial setting this fall.

She also happens to be pregnant with a baby due around the trial date. On the advice of her doctor, she asked her opposing counsel to move the trial setting to accommodate the birth. A senior lawyer at an international firm, he opposed the request, arguing that the case could be tried earlier or one of the other lawyers at Murphy Anderson could step in as lead counsel.

News of Luikart’s experience spread and is generating a bit of debate.

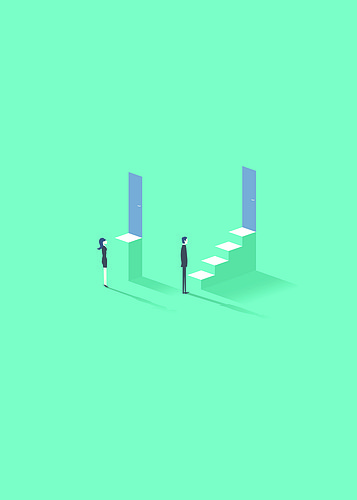

It is easy to see why: When a female lawyer from a small firm gets in a dispute with an older male lawyer from a global firm over something so fundamentally gender-related as pregnancy leave, you can find yourself in one of two camps.

Some say this is a classic example of gender bias, one that unfairly forces women to choose between career advancement and family. Others may claim it is political correctness run amok, arguing that it is entirely reasonable to oppose a motion to continue for a seriously injured client who has waited years for his day in court.

I would posit that both camps are absolutely correct.

In other contexts, the senior lawyer’s position is entirely appropriate. His client deserves his day in court, the court could advance the trial and other lawyers could easily stand in if needed.

These arguments all have validity. Yet, in this context, they fall short.

Gender discrimination exists. It is real and plays out daily in ways both large and small, patent and latent.

If the legal profession is serious about eliminating bias, then we all have to commit to act in favor of equality and hold each other accountable to this standard. We are called to exercise our discretion to make our fellow attorneys’ lives easier where we can, but when the thing we should do out of courtesy also advances the cause of justice, I would suggest that we are duty-bound to do the right thing.

Regrettably, the senior lawyer took a narrower view. Not only did the court disagree, but he was suspended by his firm for his position, which is in stark opposition to his firm’s stated values.

Worse still, he put his professional and personal reputations, built over the course of decades, in jeopardy. Some might say this is a high price for a small lapse in judgment, but after years of industry lip service and endless rationalizations that maintain the status quo, the more powerful argument supports the firm’s decision.

He had the chance to do the right thing, but he chose poorly.

In the profession, gender equity is important or it is not. If it is not, then we continue as we have, leaving such issues to lunchtime training sessions, breakouts at the occasional retreat and broadly worded policy statements.

But if it really matters, we have to demand better from ourselves and each other. We must create opportunities for women, support them in their efforts and be willing to take real action when one of our number fails to meet our collective expectations.

When we decide to behave unjustly, there should be consequences. Rationalizations offered to diminish or legitimize discriminatory behavior do nothing but perpetuate the problem.

Training designed to educate the unaware about equality issues has its place, but should be used proactively and not viewed as an easy “out” when missteps are made.

Some might argue that suspension is too severe, but if gender equity really is central to his firm’s values, what other option would suffice?

Gender equity is important, or it is not. People and institutions defend what they value and ignore the irrelevant. The legal profession has talked about this issue for long enough.

It’s time for action.